Ode to Joy: An Artistic Legacy at Saint Barnabas

The Significance of Ode to Joy

For over forty years, from 1964 to 2010, Lee Porzio’s tapestry Ode to Joy served as the focal point of every worship service at Saint Barnabas on the Desert. At 44 feet wide and 18 feet high, Ode to Joy spanned almost the entire east wall of the Sanctuary and replaced a purely utilitarian screen that covered the pipe organ for the first few years of the church’s history. The original metal organ pipe screen was held in place by a series of vertical wood beams, which had the unfortunate side effect of dampening the sound from the pipe organ. Ode to Joy, on the other hand, offered ample space for the sound to pass through its stitches and swaths—instead of detracting from the music of the worship service, the tapestry complemented it.

For over forty years, from 1964 to 2010, Lee Porzio’s tapestry Ode to Joy served as the focal point of every worship service at Saint Barnabas on the Desert. At 44 feet wide and 18 feet high, Ode to Joy spanned almost the entire east wall of the Sanctuary and replaced a purely utilitarian screen that covered the pipe organ for the first few years of the church’s history. The original metal organ pipe screen was held in place by a series of vertical wood beams, which had the unfortunate side effect of dampening the sound from the pipe organ. Ode to Joy, on the other hand, offered ample space for the sound to pass through its stitches and swaths—instead of detracting from the music of the worship service, the tapestry complemented it.

Every square foot of the tapestry offers an eye-catching symbol in a beautiful array of contrasting colors. Memorial Acceptance and Fine Arts Committee (MAFA) member Nancy Harvey has said that Ode to Joy “gathered us together and focused us on the worship service.”

The Artist, Lee Porzio

Lee Porzio and her husband, Allen Ditson, came to Arizona in 1953 and began building their reputations as artists able to work in various media. Porzio was known for her skills as a graphic artist, able to create clean designs based on her understanding of the subject and the client’s request. She also had great skills in executing her designs in various media, including textiles, paint, linoleum, ceramics, pen, and pencil. She was especially adept in textile media, as evidenced by Ode to Joy. She, along with help from her mother, Fiomena, created the monumental work of Ode to Joy out of various fabrics and types of threads. Porzio’s ancestors on her mother’s side were employed by the royal families of Italy to create textile works.

Lee Porzio and her husband, Allen Ditson, came to Arizona in 1953 and began building their reputations as artists able to work in various media. Porzio was known for her skills as a graphic artist, able to create clean designs based on her understanding of the subject and the client’s request. She also had great skills in executing her designs in various media, including textiles, paint, linoleum, ceramics, pen, and pencil. She was especially adept in textile media, as evidenced by Ode to Joy. She, along with help from her mother, Fiomena, created the monumental work of Ode to Joy out of various fabrics and types of threads. Porzio’s ancestors on her mother’s side were employed by the royal families of Italy to create textile works.

Porzio designed many of the liturgical furnishings at Saint Barnabas and Allen Ditson constructed them. Liturgical furnishings are the physical elements inside the sanctuary, like the altar and the baptismal font, which enhance and facilitate our worship. Each element works together visually, because each was designed and fabricated by the Ditson-Porzio team to integrate with the architecture and provide consistency in liturgical narrative style and an ultimate sense of unity.

In unifying the liturgical furnishings of Saint Barnabas Lee Porzio designed the vestments to complement Ode to Joy. She noted, “The symbols and colors are based primarily on the tapestry. Many of the symbols are biomorphic, with several possible interpretations… in fact, the artist hoped each viewer would absorb a mood from the work; but insert his own interpretations of the symbols.”

Over nearly five decades the Ditson-Porzio team had a close working relationship with the Memorial Acceptance and Fine Arts Committee (MAFA) of Saint Barnabas to make this possible by applying the generous memorials offered by Saint Barnabas parishioners to fund the commissioning of each work. This system of funding is a hallmark of Saint Barnabas. All of the memorials that have been given over the years are recorded in the Memorial Book in the narthex. Funding for the conservation work that was done on Ode to Joy and the digital recreation project was provided by the Charles Dunlap memorial fund.

The collection of sanctuary furnishings by Ditson-Porzio Studio includes the altar, cross, ciborium, candelabra, chairs, candleholders, verge, baptismal font, urn stand, alms basins, acolyte’s torchiers, flower stands, missal stand, ambry, credenzas, litany desk, organ cover, and stations of the cross, as well as a wide variety of liturgically seasonal sets of vestments and hangings. Lee Porzio designed and stitched the tapestry and many of our vestments. Her creative genius provided the design for the chair cushions, kneelers, and banners. Our liturgical furnishings continue to serve us every week and will do so for decades to come.

The collection of sanctuary furnishings by Ditson-Porzio Studio includes the altar, cross, ciborium, candelabra, chairs, candleholders, verge, baptismal font, urn stand, alms basins, acolyte’s torchiers, flower stands, missal stand, ambry, credenzas, litany desk, organ cover, and stations of the cross, as well as a wide variety of liturgically seasonal sets of vestments and hangings. Lee Porzio designed and stitched the tapestry and many of our vestments. Her creative genius provided the design for the chair cushions, kneelers, and banners. Our liturgical furnishings continue to serve us every week and will do so for decades to come.

Porzio had a very successful career as an artist and her creations grace not only Saint Barnabas, but were also installed around the country. One of her works, Corona, is displayed in terminal 3 at Phoenix’s Sky Harbor airport. The scale of Ode to Joy certainly qualifies it as one of her masterworks. At the bottom of the piece Lee stitched her name and the dates of inception (1962) and completion (1964).

Construction of Ode to Joy

Ode to Joy was conceived by Lee Porzio in 1962. The work was completed and hung by her husband and artist Allen Ditson on the east wall of the sanctuary for Easter Sunday, March 29, 1964. The Ditson-Porzio Studio was located on Doubletree Road in Paradise Valley and Allen rolled up the piece and brought it to Saint Barnabas in the back of his truck. The first time it was seen in its entirety was when Allen hung it from the roof of the sanctuary on the outside of the east wall before moving it inside the sanctuary. Along with the architecture, Ode to Joy was the dominant visual element of the Saint Barnabas sanctuary.

Throughout its years hanging in the sanctuary, Ode to Joy was often called simply “The Tapestry.” Lee Porzio herself referred to it as a tapestry, when in fact, it is technically not a tapestry at all, but rather a collage. A collage is a technique of creating art by attaching a diverse assemblage of elements in a juxtaposition on a background for effect. A tapestry is a woven material into which the design is woven during manufacture. However, oftentimes a work of art, executed in fabric and hung on a wall, whether a collage or not, is called a tapestry.

Porzio used rolls of brown open-weave Irish linen material, which were about three feet wide, as the backing for the work. A popular story surrounding the tapestry is that the Irish linen Porzio used was the same as fabric used to line sports jackets and the supplier in New York wanted to know what someone needed 90 yards of the material for. Other fabrics Porzio incorporated into the work included silk, nylon, organza, chiffon, net, and lamé. The sewing and weaving threads are linen, mercerized cotton, nylon, silk, wool, and metallic.

The cutout shapes in fabric were then sewn onto the linen. Some of the shapes are themselves made entirely out of stitching! Lee said that she thought every known embroidery stitch was used in Ode to Joy. Lee worked on the piece in her studio, working from a small cartoon she had drawn. Porzio did not use any patterns for the myriad shapes in the tapestry, instead cutting out each shape by hand using scissors. Many of the shapes overlap other shapes and in some cases, there are many overlapping shapes that make for a very challenging design to construct. Yet the various shapes are easy to identify on their own. In some places, there are as many as seven overlapping layers of fabric. This required extensive planning and effort to bring together the panels and sew the fabric collage pieces between panels. Also note that she created stitched lines that extend dozens of feet long across the design. A careful inspection will reveal the names of several people associated with Porzio and the MAFA Committee at Saint Barnabas sewn into the design.

Once the three-foot wide sections were completed, they were themselves stitched together using a sailor stitch and the overlaying patterns were stitched onto the adjacent linen panels. It is difficult to imagine the complexity of all the stitching patterns that were essential in the design. Some of the stitching patterns Porzio used are over 30 feet long. She used a method of scrolling the material in her studio so that she was able to work on such a large piece. As she worked, she would scroll up or down in the design.

The Theme of the Work

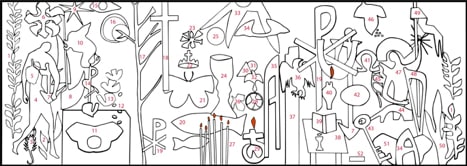

Lee Porzio brought a strong understanding of the symbolism used in Christianity to her work. Ode to Joy’s meta-narrative—the broader story it tells in conjunction with the sanctuary in which it hung—progresses from left to right in four visually flowing but distinct sections: The Creation, The Fall, Resurrection/Redemption, and New Creation. The central theme of Ode to Joy is the resurrection, which is also at the center of our faith. Traditional Christian symbols like the cross and the Alpha and Omega are immediately recognizable, and paired with more secular symbols of creation and new life, like the leafy plants on the left side of the tapestry and the butterfly near the center.

The Creation is represented by symbols like figure 1, leafy branches which represent the Garden of Eden at the beginning of our relationship with God. The Fall is symbolized by images such as figure 4, the hunched-over figure of man, and figure 5, the apple. An apple in the hands of Adam meant disobedience to God, but in the hands of Christ, it symbolizes the fruits of salvation. Apples were one of the primary trees cultivated in ancient times. In the center of the tapestry we see the chalice and wafer (figures 24 and 25), representing both Christ’s sacrifice and the center of our Christian faith and liturgy, the Eucharist. Images on the right like the eagle (figure 36) and the egg (42) symbolize the Resurrection. New Creation is represented by images like the figure of man on the far right (figure 47), portrayed in his risen state after the grace shown by resurrection.

The complete listing of the symbols and their meanings can be found in the legend cartoon and legend document These descriptions were taken from Lee’s legend cartoon descriptions.

Preserving the Tapestry

Textile conservator Martha Winslow Grimm was employed in 2006 and 2009 to clean Ode to Joy and do some fabric repairs to help lengthen its life. Her report on the condition of Ode to Joy indicated that some of the fabrics were not expected to hold up much longer. In 2006 a proposal was first made to systematically photograph Ode to Joy in great detail.

In 2009, Ode to Joy was extensively photographed to document the piece in high detail, so that possibly in the future either conservation work or a digital re-creation could be made. As planning for the Sanctuary Project proceeded, it became clear that removing the work and undertaking a complete conservation effort to restore it so that it could be reinstalled was not practical in terms of time, cost, and effort required. The damage to some of the fabric, in particular the synthetic gray and red colored fabric, would require that all of the pieces made of these fabrics be removed and replaced. When it became clear that some of the fabric in Ode to Joy was deteriorating beyond the ability to repair it and that the original pipe organ behind it needed to be replaced, it was decided to retire the piece.

From the over 300 photographs taken of the tapestry an effort was undertaken to create a digital photograph of the entire piece that would show Ode to Joy as it originally looked in 1964 before it was hung on the wall behind the columns. This was a three-part process:

First, photographs of sections of Ode to Joy were digitally stitched together using Auto Pano Giga software to create one continuous photograph of the entire Ode to Joy. Second, the file created was worked on using Photoshop to repair digitally all of the fabric tears throughout the piece. Third, Photoshop was then used to restore the vibrancy of the original fabric colors that had faded from UV light damage over the years.

The finished file was then used to print on special canvas using archival inks. The largest practical printed size is 8 feet long. Any larger and the resolution degrades noticeably. It is also possible to print on metal, which offers better colors and resolution.

An advantage of the digital recreation is that it will enable future generations to experience the complexity and richness of Ode to Joy, even though the original is out of sight. Also, one can easily view the smaller canvas version up close. The size of the original piece meant that from eye level, viewers were  over 20 feet away from all of the symbols at the top of the piece near the ceiling. The digital recreation brings those symbols down to eye level and allows people to fully experience the piece.

over 20 feet away from all of the symbols at the top of the piece near the ceiling. The digital recreation brings those symbols down to eye level and allows people to fully experience the piece.

With the decision to remove Ode to Joy and place it in storage, planning and research was done into how best to conserve it. Several textile conservators were consulted and a plan was conceived to both remove the work from the wall and store it, so as to minimize damage.

In January 2010 Ode to Joy was transferred from the wall to an engineered pivoting steel and wood frame. This frame allowed the work to bend enough to pass through the arches and move across the floor, supported from above by lifts. The strength of the background linen holding the work together made this possible. As the work was moved it survived intact, with no damage. It was moved to where the pews had been, lowered flat onto tables and carefully rolled onto a rotating cylindrical form that was covered in flannel. It was then covered in muslin by textile conservator Martha Winslow Grimm and later moved into storage in the music building. In 2014 it was moved into storage at Bridging Arizona in Mesa, Arizona. Ode to Joy had remained in place from Easter Sunday, 1964 until January 10, 2010, almost 46 years!